Heat, Death and Loneliness

Anastasia Mortimer & Dr Glenn Shea

08.10.2017

The Living Room Theatre’s latest work in development ‘Anastasia’, explores death as an outcome of heat waves in shock climate events.

The exploration of death has led to Michelle St Anne pondering the human body’s physical responses to death. What happens to the body when we die? What is the human body’s process of shutting down? How does the body decompose?

Discussion of the physical components of death is often considered taboo, and traditionally only deemed acceptable in medical contexts. And yet, death is a shared experience that every living being will inevitably experience. This truth it is sparsely discussed, and St Anne aims to shed light on the physicality of death by applying scientific information on the topic and translating it through the medium of theatre.

St Anne’s ‘Anastasia’ death series is a component of the larger project ‘Anastasia: Communicating heat & climate vulnerability through performance’, funded by the Pop-up Research Lab scheme awarded to the Sydney Environment Institute in partnership with The Living Room Theatre, by the Sydney Social Sciences and Humanities Advanced Research Centre (SSSHARC).

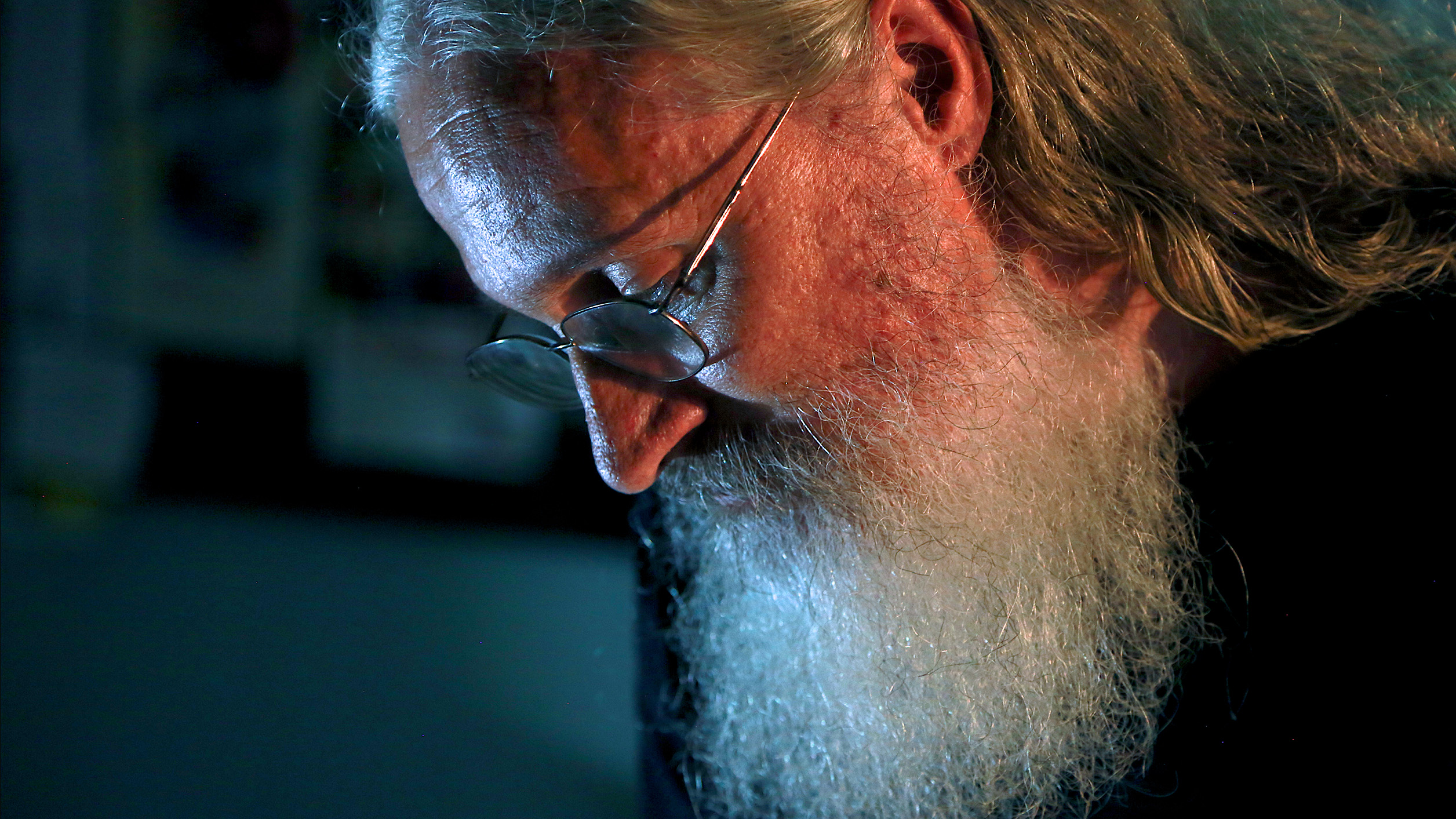

In an attempt to understand and communicate the physical aspects of death, St Anne plans to draw on the expertise of Dr. Glenn Shea, Senior Lecturer in Vet. Anatomy & Pathology at the University of Sydney, who is a collaborator on the project. Shea explains that the key to understanding the physical process of death and what happens to our bodies when we die, is to understand what is happening in the living body.

Vast numbers of individual living cells exist in a living body, and the myriad of living cells are facilitated by the cardiovascular system. In order for a living body to function, bodies require a working cardiovascular system.

In life, the cardiovascular system transports oxygen, obtained from the respiratory system, and nutrients, obtained from the gastrointestinal system, to all the cells of the body (including those of the respiratory and gastrointestinal system), and removes waste products, transporting them to the kidneys and liver (in the case of waste products from nutrients) and the lungs (in the case of carbon dioxide) for excretion via a number of processes.

As death approaches, the cardiovascular system becomes less efficient in functioning, and the supply of oxygen and nutrients is reduced, while the removal of waste products is hampered. The nervous system, which is also involved in the regulation of the cardiovascular and other body systems, and is a highly metabolically active, begins to malfunction as its supply of nutrients and oxygen is affected in turn affecting all other organ systems that it normally regulates, including the heart, which contracts less effectively as its cardiac muscle weakens.

The urinary system, which normally filters out the waste products received by the blood, similarly becomes less effective as the blood supply to the kidneys is reduced, causing waste products to build up in the blood to toxic levels. Muscles similarly become weaker and less responsive as their nutrient supply and their nervous control become abnormal. Respiration, which involves muscles contracting and relaxing under nervous control, becomes less effective, and so oxygen supply and carbon dioxide removal become abnormal. The result of all of these changes is derangement and ultimately death (at a variety of rates) of all of the cells in the body.

Shea was also asked what is the last part of the body to stay alive after death, and explains, that once we die, the decomposition process begins:

Decomposition is a slow process involving many steps. The first stage, during which the body’s cells die, involves breakdown of the body’s tissues by bacteria. Our gut has vast numbers of bacteria, continually digesting food and producing gas as a byproduct (which we fart and burp during life). Once the wall of the gut dies, bacteria start to digest this supply of new food, weakening the intestinal walls. As gas builds up, the gut, weakened by breakdown, tears, and bacteria are able to invade the abdominal cavity, continuing to find new resources to exploit.

The body’s cells die at different rates, largely dependent on whether they are normally actively metabolising cells that require a continual supply of nutrients, or are slowly metabolising cells that normally have a limited supply of nutrients. The latter include the cells of dense connective tissue, such as cartilage, bone and tendon (which is why it is possible to obtain useful transplants of these tissues for several hours after death). The down side to such a low metabolism is that these tissues also take long times to heal in the living body. Eventually, all the body’s cells are dead and break down, releasing lots of fluid into the tissues, which lose structure, and the bacteria continue to proliferate as they consume the dead tissue and nutrient-rich fluid, producing even more gas.

St Anne’s curiosity over what happens to our bodies when we die is linked to a desire to communicate how a heat wave has physical implications on the ability for our bodies to function. However, St Anne’s curiosity with the topic of death in the forthcoming ‘Anastasia’ series does not solely focus on the physicality and process of death, but will also explore the ethical and emotional aspects.

St Anne’s ‘Anastasia’ series is based on a desire to communicate death as an effect of heat waves, which will occur more frequently as a consequence of climate change. Shock climate events such as heat waves will impact the most vulnerable people in the community, and this is at the heart of the ethical dimension of St Anne’s work.

Furthermore, St Anne sees the physicality of the decline of a bodies’ functionality during the precipice of life and death as a metaphor for the death of Mother earth through climate change. The anthropomorphism of the earth provides us with an understanding or reference point as to what is happening to our planet as it declines in functionality and how she draws her last breath. St Anne will explore this metaphor throughout the ‘Anastasia’ series.

The first event in the project is ‘A Requiem for Anastasia’ – an artist talk and showing by St Anne, who will offer insight into the earliest stages of the theatrical knowledge translation process, exploring this idea of performance as an innovative means of mobilising research surrounding shock climate events and their impact on vulnerable communities. For more information and tickets, click here.

You can discover more about the work in development here.

This article contributes to research of the Anastasia Project and was originally published by the Sydney Environment Institute at the University of Sydney.