The Black Summer & Time, Grief, Memory, Value

Michelle St Anne and Gemma Viney

15.01.2022

‘Dark Interludes’ is dedicated to the many named and unnamed

A woman face down, body askew

Double bass necks yearn for the sky

Ash collected, passed and restored to home

The 2019/2020 bushfires – The Black Summer, named, unlike vast swathes of the life which succumbed to it – constituted one of the most devastating natural disasters in Australia’s history. They engulfed the countries’ North and South coasts, the far West and soon raging fires erupted across the continent, obliterating everything and leaving a profound effect on communities.

As we face the ever-increasing likelihood of environmental disasters resulting from climate change, we will be continuously confronted by the question of how we account for the harms implicit in aftermaths. How do we ensure that, as with these fires, loss of life and of home is not devalued – deemed unworthy of calculation – in the state’s attempt to account for lost capital.

As the fires raged the sky turned surreal and unfamiliar with an eerie undertone. Far from the fire front, in the suburbs of Sydney we experienced the Sun in a new way. A different light bled through the streets and crept through our windows. We woke to a different palette of oranges and reds, peering through “a ruddy gloom”1.

Here it was: my life’s work, in the sky – the beauty of horror and horror of beauty – my body in heightened form, with the inconceivable blaring through my imagination.

Encroaching fire fronts hemmed in Communities across the country, leaving us with visceral images of those driven to the edge of beaches and kangaroos, ablaze, seeking refuge in the sea. The fear that had enveloped the country was palpable. In the cities people walked about dazed, covering noses and mouths muzzled, their words not fit for purpose because what could be said? A heating planet – this was inevitable.

The confronting stories and images built a cacophony of noise before its release.

Before the recovery.

And like all climate disasters it would soon be all over and what of it would we remember?

I needed to make a work to capture this silence of the darkened, still world and acknowledge the many unnamed.

One loss that we have failed to consider in calculating the costs of the Black Summer, is how the fires will impact our outlook. Our relationship to the sky, and to summer, has changed. There was an oppressive sense that this could be our reality from now on, and the smell of smoke – which was once a familiar and relatively warming reminder of the end of the year – has become a far more ominous trigger point. With this, our attachment to place shifted, irreversibly so and far more menacingly for those under direct threat from the fires.

“The fire basically came right through our village. After we evacuated, we thought our house had gone, but we were told the next day that somehow it survived despite the fire actually licking at the sides of its concrete slab. But unfortunately, the rest of our home, which is all of the, you know, beautiful trees and shrubs and plants and animals and everything that we share it with didn’t survive.” – Julie Vulcan

‘Dark Interludes’ is a collaboration between performance artist Julie Vulcan and myself.

Together we had just created two responsive performances pieces for Requiem, an exhibition curated by artist Janet Laurence. Our two works bookended the exhibition, opening with Julie’s durational performance, ‘Rescript’, that explored her own distressing encounter as the fires threatened and then tore through her community.

Julie painstakingly, and with enormous care, collected the ash of her scorched home and its multispecies inhabitants. ‘Rescript‘ gave the ash devotional care through a ritual of embalming, undertaken over several hours, as audiences were invited to witness the slow, almost timeless, practice of mourning and remembrance.

My piece ‘Myosotis’ was a funeral of sorts for those bodies not ‘counted’ and largely forgotten, as they did not possess prescribed economic value.

‘Dark Interludes’ brings these two works in concert with each other in filmic form. Whose body do we value, care for, celebrate, mourn? What bodies count in disaster data? Climate catastrophes trigger calculations of the cost of human life, of homes, livestock and livelihoods – but how do we account for loss.

Scholarship would have us understand that place is tied to culture, to ways of life. However, our current accounting for the losses of communities dislocated by disaster fails to capture the damage to people’s lives if they are forced to leave or are left behind.

When mining companies, for example, drive individuals out of place, we capture the impacts to property pricing, livelihood and even the prospective economic benefits a community might see resulting from an incoming workforce.

What often goes unseen is the devastation of a fractured socio-cultural landscape, what Askland and Bunn (2018)2 describe as the slow ‘death’ of small rural communities. Crucially, even those who stay experience a social dislocation that leaves them feeling lost or ‘displaced in place’.

Place, repetition, duration and ritual fascinate both Julie and I as artists and thinkers.

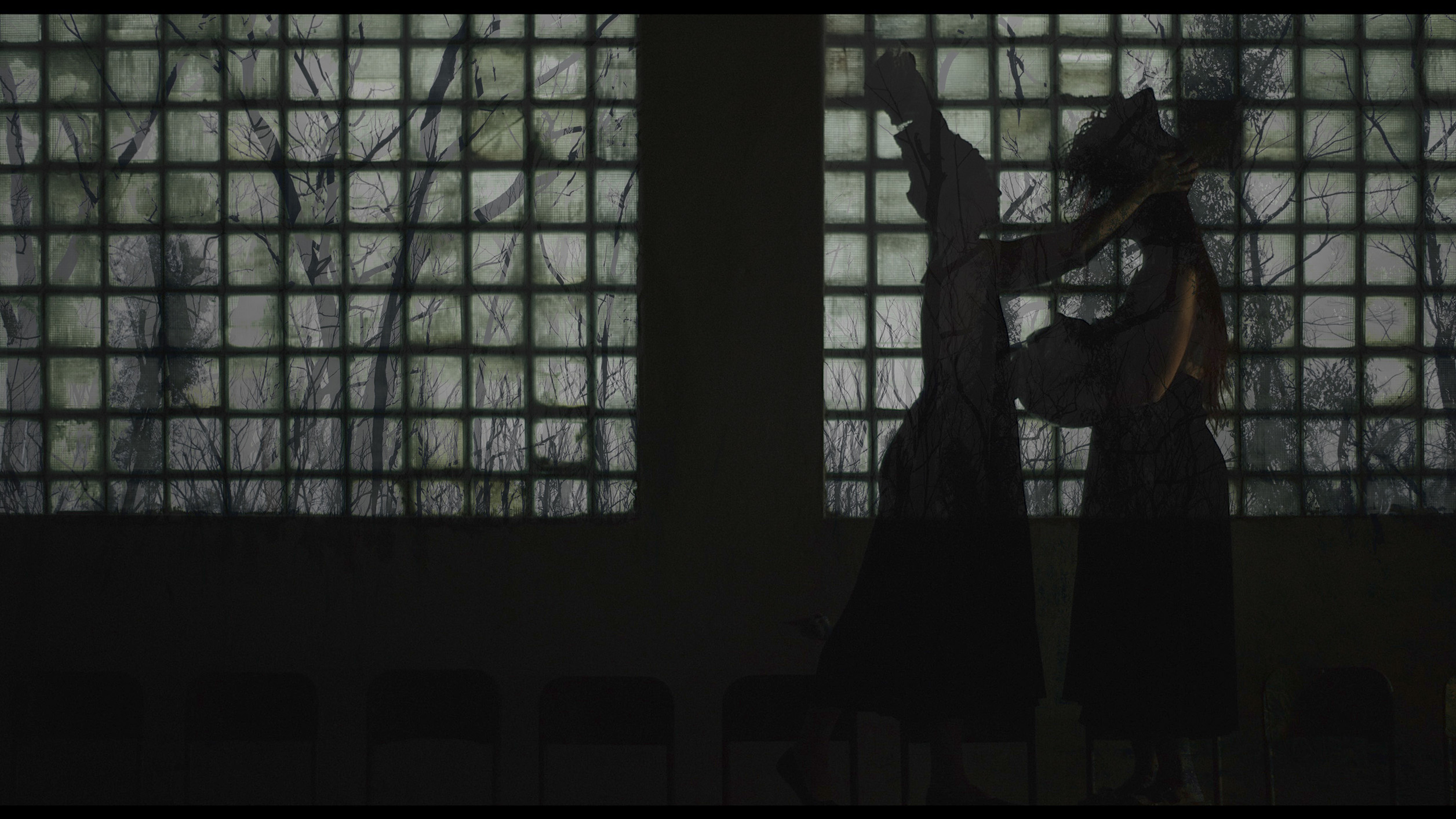

The film opens with a woman’s body face down on a bed. I placed myself inside this scene to speak to this question of value. By tying myself, a woman of colour, to this image I quietly tap into the viewer’s unconscious bias. How do they receive my discarded body? Is it something worthy of their sympathy; worthy of their care? Dressed in a pink gown, the colour is a nod to a woman who died on a cruise ship, referred to as a ‘black pig’. I am haunted by this story of Dianne Brimble and fragments of her appear in a series of my works.

Three double basses are playing ‘abbandonatamente’ (freely, in relaxed mode) as if chaperoning the ghosts free. Between them, Imogen Cranna arrives as the Mother Spirit of trees, her elongated headpiece3 echoing the neck of the double bass as if predicting their demise. Sonic artist Amanda Stewart, who reappears in the final scene without body, hauntingly voices her.

In the coming repetitive frames we watch as Julie embalms my body with the ash from her home. Those collected bodies becoming one with mine, before being ceremoniously bundled and passed through to the next life.

The next home.

We find ourselves returned to the landscape of Julie’s home amongst those spared by fire. Working with film artist Sam James, we shot Julie’s property from down low in order to capture the elevation and expanse of the towering burnt trees – the new life emerging–against the starkness of the sky.

The soundscape of this work is about absence. The staccato of double basses, now five, are plucked and pinched – a series of short, sporadic, muzzled sounds of a gasp capturing the quiet guzzling for breath and the death of species not heard under the roar of a fire.

The sound of Stewart’s Mother Spirit comes to the sonic foreground as the basses dissipate and disappear from the landscape to become the voices of the unnamed.

As Julie returns the Lost through the repetitive ritual of caressing and placing back into landscape, into home, sound designer Ashley Scott bleeds out Stewart’s voice, and we are alone with the silence of an emerging world. Of the quiet of new life – giving voice to the voiceless and reminding the audience to look beyond the traditional idea of performer and to recognise that the landscape is as equally weighted and present in the piece.

Conceived and created in two weeks, ‘Dark Interludes’ was a true collaboration between performance makers, a film maker Sam James, sound designer Ashley Scott with Double Bass players Maximillian Alduca, Marie-Louise Bethune, Jacques Emery, Dave Ellis and Will Hansen with the elegance of my long-time collaborator Imogen Cranna.

The whole project relied so heavily on trust, and the result is a broody work about time, grief and memory and tests concepts of calculation and value. It’s a testament to artists who can speak across themes and textures, and a tribute of fearlessness and trust within an ensemble to voice the unnamed with the named.

References

1. Quigley, K 2020, ‘The End of the Beach’, Sydney Environment Institute.

2. Askland, H & Bunn, M 2018, ‘Lived experiences of environmental change: Solastalgia, power and place’, Emotion, Space and Society, vol. 27, pp. 16-22.

3. The headpiece was crafted by milliner Rosie Boylan.

Co-authors Michelle St Anne and Gemma Viney

Gemma Viney is a Research Assistant on the FASS 2018 Strategic Research Program Project developing the field of Multi Species Justice and is currently completing a PhD in the Department of Government and International Relations.

Gemma was an Honours Research Fellow with the Sydney Environment Institute in 2017. She has a Bachelors degree in International and Global Studies from the University of Sydney, and a First-class Honours Degree in the Department of Government and International Relations.

Gemma Viney is the Research Lead on Anti-Mining Community Movements at the Sydney Environment Institute.

The is article was originally posted by Sydney Environment Institute

It forms part of the Sites of Violence project which merges artistic and academic understandings of human and non-human experiences of violence, and the processes, emotions, and meaning that this violence reveals. This transboundary approach dismantles learned indifference by introducing novel perspectives to old problems, and facilitates productively disruptive collaborations between researchers and artists.